He wanted everybody in and nobody out

honors the decades-long legacy of Chicago's Dr. Quentin Young.

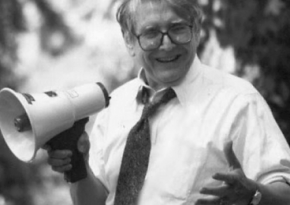

DR. QUENTIN Young was a health-care reform rock star. He coined the deceptively simple slogan "Everybody in, nobody out" to encapsulate the idea that every human being has the right to guaranteed health care.

That notion has sunk into national consciousness. And it's a testament to Quentin's indefatigable efforts and influence that in the current election cycle, the advantages of a national, single-payer health care system is being discussed once again.

We lost Quentin Young on March 7. He was 92.

As a left-wing activist from an early age, Quentin was on the right side of all the struggles for equality, from workers' rights to the civil rights movement in the 1960s to the fight against the so-called "war on terror."

Quentin is probably most widely known for his commitment to implement a health care system in the U.S. that put patients first, not the profits of the health care industry. And always and everywhere, Quentin exposed the stark and disgraceful racial disparities in the American health care system.

Quentin was a founding member of Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), and it is one of his most enduring legacies. The existence of PNHP is critical to the fight for a single-payer health care system and to keeping alive the idea that health care is a human right. It is truly sick that in the richest country in the world, this idea must continually be asserted. For 22 years, Quentin was PNHP's national coordinator, and the organization has grown to 20,000 members.

I HEARD about Quentin Young long before I met him. I picked up a copy of Hospital: An Oral History of Cook County. In the book, Quentin details the pervasive corruption and patronage at Cook County Hospital, he explains the fierce esprit de corps that existed among County medical staff, and he reveals why patients felt that County was their hospital.

Young was Cook County Hospital's chair of medicine from 1972 to 1981. Under his leadership, the Occupational Health Service (OHS) and the Jail Health Service (JHS) were established. He writes of the OHS: "Most schools of occupational health essentially trained company doctors; we stressed that this was a worker-orientated occupational health program."

Quentin was especially proud of the doctors who worked in the JHS, writing, "These doctors stood ready with the Prison Health Project of the ACLU and the Carter administration, and the Justice Department to be expert witnesses on the conditions in numerous jails and prisons in the country where lawsuits were brought."

County bosses tried to fire Quentin for his outspoken activism, but Quentin wasn't having it and refused to leave. The door to his office was padlocked. His house staff took the door off the hinges and occupied the space. Attending doctors were ordered not to recognize Quentin as chief, but no one else would take his job. In a show of solidarity, 40 doctors made rounds with him. This was the kind of respect and loyalty that Quentin inspired.

Many years after Quentin worked at County, I took a position as a social worker in the emergency room at the new John Stroger Hospital, the replacement for County, and then in Fantus Clinic. Patients who were overwhelmingly poor, Black or Latino presented in such poor health it was staggering.

How was this possible in a wealthy city like Chicago that had no shortage of medical resources and infrastructure? Quentin explained why in Hospital:

I used to say there was no room for liberals at County. Only two world philosophies worked with what you saw before you, because the wretched of the earth: alcoholics, drug users, late-stage disease, people with wound infections with maggots in them--I mean really bad. And so you could come up with two conclusions...the one I and many of us embraced–that this was the distilled oppression of society. These were people on the bottom of the economic heap, of racial discrimination, who were born to lose, and their whole life is a testimony to privation, oppression, and what we are seeing is the physical expression of it.

When I read those words, I understood the social determinants of health on a whole new level and found a further depth of empathy for my patients.

Some days, it felt like the emergency room or the clinic was a war zone, and the unnecessary human suffering, the premature death was too much to bear. I would call Quentin. One time he said to me: "You are seeing the contradictions in their rawest form. The oppression is all around you. Very few situations are like that." And then he'd get nostalgic and tell me stories about the glory days of County.

I STARTED writing about health care and interviewed Quentin on many occasions. I got to know him better during the years when the Obama administration developed health care legislation. He spoke at dozens of rallies and meetings.

By a certain point, Quentin wasn't able to drive anymore--something that really pissed him off--so a group of volunteers drove him to speaking engagements. On the way back after a meeting, we dissected what happened, and I told him he was too soft on people who raised ridiculous arguments against single-payer. He laughed and said people often told him he was too hard on his opponents. But Quentin was the kind of person who listened and took what others thought seriously. He said, "Okay Helen, next time I'll be harder."

Quentin refused to support Obamacare despite enormous pressure to do so. The small advances in the law, like regulations against insurances companies pre-existing conditions to reject applicants, paled in comparison to the measures that gave even more power to for-profit health care and capitulated on the vision of "everybody in, nobody out."

He was accused of being pie-in-the-sky. Liberals who formerly supported single-payer scolded Quentin and said it was never going to happen in America, so just get onboard with the president. Over and over, the hackneyed phrase "Don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good" was hurled at him.

But Quentin said no. In a world where leaders of social justice movements too often buckle under the pressure to accept crappy, piecemeal reforms that help the fewest people, Quentin Young stood apart for refusing to concede.

To be in Quentin's presence was to be in the presence of greatness. His greatness was the opposite of what is traditionally thought of as greatness--where a person exerts power and control over others and has a gigantic ego. Quentin's greatness was grounded in his profound humility, his love for humanity and in his lifelong fight for health care justice and equality for all.